Landscape in quotes: Olga Bezhina’s paradox painting

In the history of art there are many examples of self-restraint. Offhand, I recall the association of writers and mathematicians ULIPO, one of whose participants, Georges Perec, wrote the novel La Disparition (1969) without the most frequent French letter “e”. The minimalist artist Saul Levitt called the cube the basic unit of his creativity, and Jackson Pollock, the leader of abstract expressionism, sprayed paint from his brushes onto a huge canvas on the floor.

In the history of art there are many examples of self-restraint. Offhand, I recall the association of writers and mathematicians ULIPO, one of whose participants, Georges Perec, wrote the novel La Disparition (1969) without the most frequent French letter “e”. The minimalist artist Saul Levitt called the cube the basic unit of his creativity, and Jackson Pollock, the leader of abstract expressionism, sprayed paint from his brushes onto a huge canvas on the floor.

In general, in truth, any artistic direction, as well as the unique style of the creator, is a system of conscious or unconscious restrictions. The idea of infinite freedom of the artist – no more than fiction. Ultimately, freedom is a conscious choice between restrictions, and even the creation of these restrictions for specific goals and objectives (the latter are included in certain ideological attitudes). However, any restriction is also an opportunity, therefore, if you please, replace the previous sentences with one another.

Creativity Olga Bezhina in this sense is no exception. She offers the viewer an original image technique, not as radical as that of Pollock, but no less interesting. But what can such a self-restraint (drawing with the finger of one hand) give the viewer? What doors of perception open these mosaic pictures?

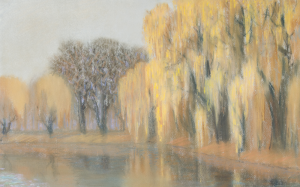

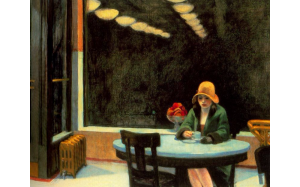

Obviously, the artifact exists in two planes: in the real, objective dimension, in all its truth inaccessible to us, and in the dimension of our perception. The most interesting thing in Olga Bezhina’s “landscapes” is precisely this moving border between what is and what seems. These pictures literally change before our eyes, one has only to move on or, conversely, to come closer. At arm’s length, they turn into chaos of oil paint, an insane dance of color spots, but, having chosen a respectful distance, chaos suddenly crystallizes into a certain order. The pictures, as it were, include an observer who unwittingly becomes a participant in the creative game, constantly shifting and fixing the point of view. And it is not necessary to look at the picture at right angles. I tried to look at the image obliquely, as if looking out from behind a subframe, and it was already a completely different picture with its own visual effects. The classic landscape would even be upside down.

Another interesting feature of Olga Bezhina’s coarse-grained, one-finger oil works is their flatness, lack of perspective, depth, and articulation of objects (the latter is achieved by “discriminating” lines in favor of raster color diversity). This is a homogeneous visual environment, an imprint of feelings, the transfer of expressive means of the emotional mood of the artist, which arose in contact with nature, the city, the hippodrome. The psychological concept of “gestalt” (a holistic perception of an object that is not reducible to the properties of the sum of its constituent elements) is well suited to describe these pictures. The whole in painting by Bezhina dominates the parts, which, like echoes or subtle hints, appear at a distance (an involuntary allusion to the poet’s lines). For the time being, they hide in abstraction of pure color.

In general, the painting of Olga Bezhina is curious with just such a paradox: simplicity and complexity, realism and abstraction, “spotting” or linearity. Multidimensionality and multivariate perception. This space without time, has become a task.